With the use of the phrase ‘Bangladeshi language’ by a Delhi Police officer creating a political storm, BJP IT cell chief Amit Malviya has stepped in to school West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee on the nature and development of Bengali language. His long X post offering detailed linguistic commentary, however, shows little understanding of how not only Bangla, but any language grows, evolves and survives.

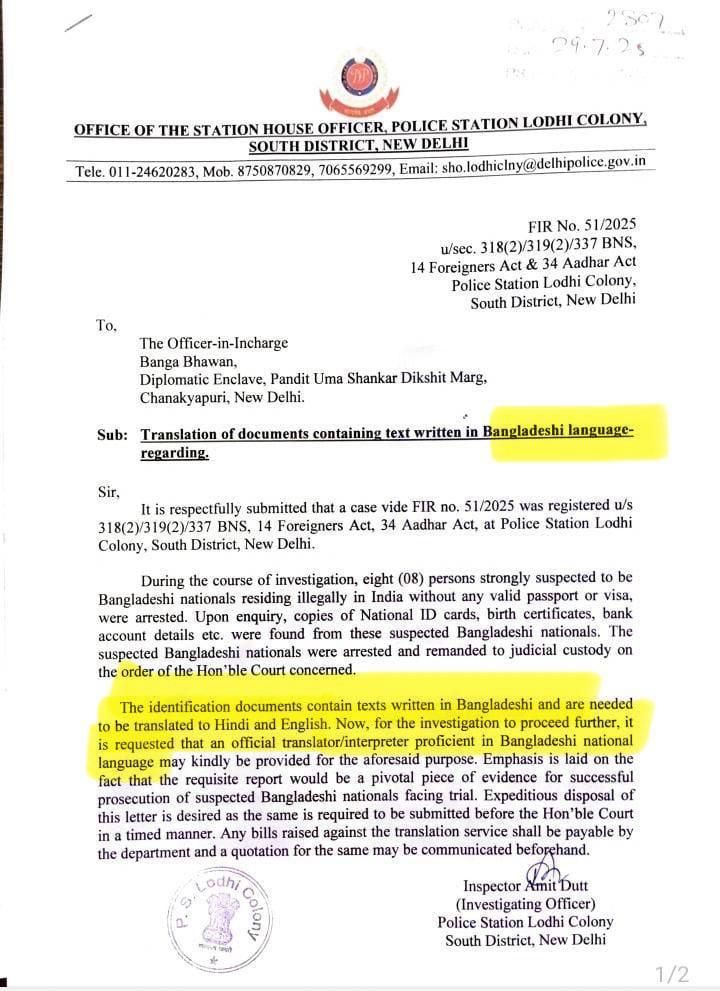

The controversy began with a letter surfacing on social media about a week ago in which Amit Dutt, an inspector at Lodhi Colony police station, sought help from Banga Bhavan officials in translating “text written in Bangladeshi language” in connection to the arrest of eight suspected Bangladeshi nationals.

The discovery of the letter comes against the backdrop of reports of alleged harassment, detention and torture of Bengali-speaking migrant workers, particularly Muslims, in several states in the last couple of months or so, on the suspicion that they are illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. Things came to such a passe that entire colonies in Gurugram in BJP-ruled Haryana, where Bengali-speaking labourers and gig workers lived for decades, saw mass exodus in fear of detention. Detentions and torture were reported from states like Assam, Odisha, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, all of which are ruled by the BJP or its allies. In Assam, chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma declared that mention of Bengali as mother tongue in public documents will help the government in identifying foreigners.

In this context, the letter was deemed by many as yet another affront to Bengali speaking people. Terming the letter “Scandalous, insulting, anti-national, unconstitutional” West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee took to the streets protesting against what she called an “insult(s) (to) all Bengali-speaking people of India”. Tamil Nadu chief minister Stalin, too, called it a snub to the language in which the country’s national anthem was written.

Enter Amit Malviya, the Linguist & Logician

Responding to Mamata’s X post condemning the Delhi Police letter, Malviya, who is BJP’s West Bengal co-in charge, shared a long ‘explainer’ on X (formerly Twitter) defending the use of the phrase ‘Bangladeshi language’.

Mamata Banerjee’s reaction to Delhi Police referring to the language used by infiltrators as ‘Bangladeshi’ is not just misplaced, it is dangerously inflammatory.

Nowhere in the Delhi Police letter is Bangla or Bengali described as a ‘Bangladeshi’ language. To claim otherwise and… https://t.co/Ynb5o8cT6n

— Amit Malviya (@amitmalviya) August 4, 2025

Almost everything that Malviya has stated about Bengali language in his post is false from the point of view of language study. We shall focus on these claims — four of them to be precise — made in the fourth and fifth paragraphs of the X post. We will fact-check them one by one, sentence by sentence.

Claim I: “… Dialects like Sylheti (that) are Nearly Incomprehensible to Indian Bengalis”

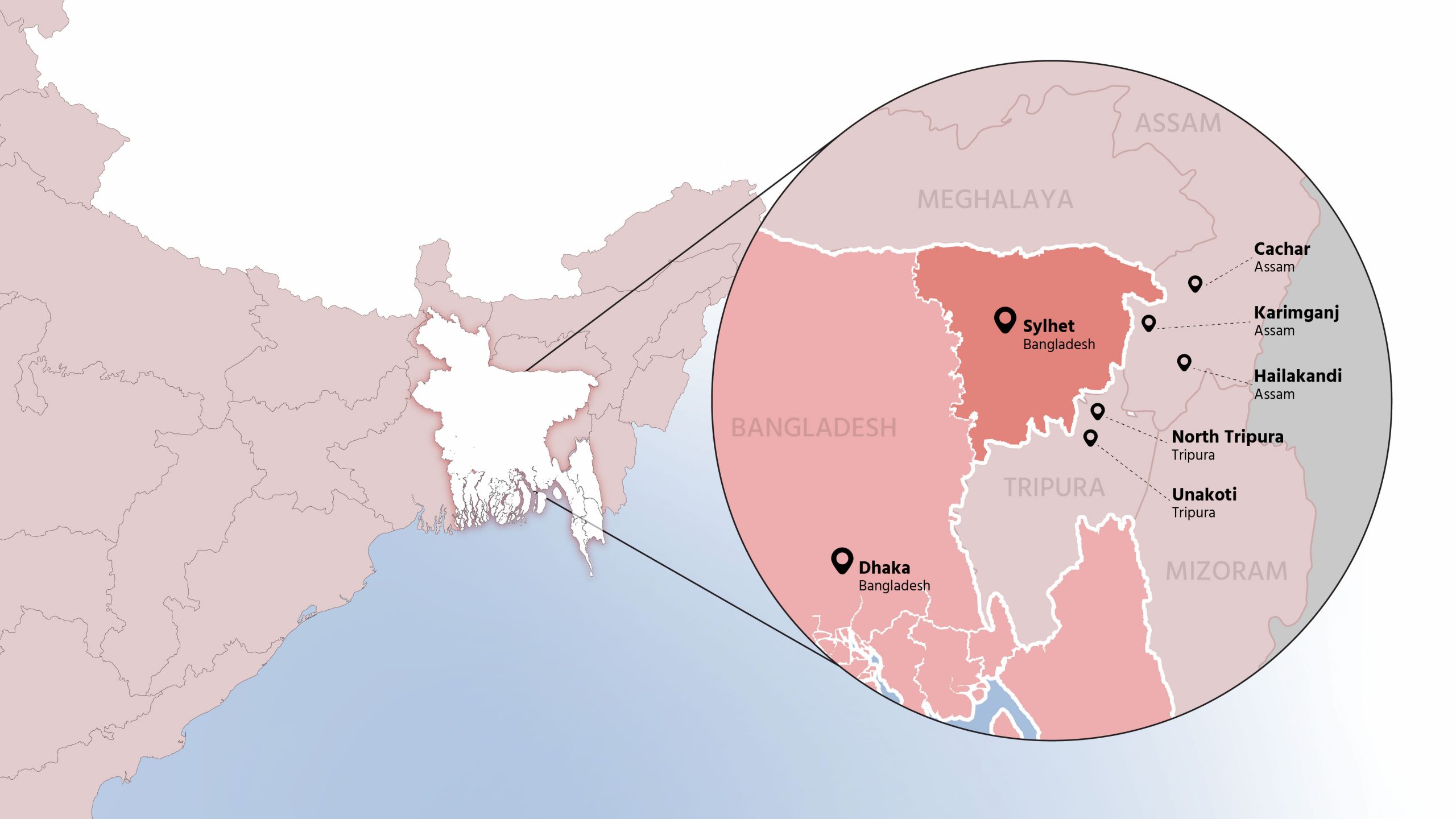

The Sylheti language, which derives its name from the province of Sylhet, is primarily spoken in the Sylhet division in the northeast of present-day Bangladesh. Divisions are the first level of administrative hierarchy in Bangladesh, the entire country being divided into eight of them. Sylhet division has four districts: Habiganj, Moulvibazar, Sunamganj, Sylhet. Sylheti is spoken in all four of these districts. However, Sylheti is not spoken in only these areas.

Being a border division, Sylhet shares international border with Assam, Meghalaya and Tripura states of India. See map below:

Sylheti is widely used by people residing in the Barak Valley division of Assam, as well as several north Tripura districts, who identify themselves as Bengalis. Barak Valley division in Assam comprises three districts: Cachar, Hailakandi, and Karimganj. Sylheti is spoken by Bengalis in all three of them. In Tripura, which is the other Bengali-speaking state after West Bengal, Sylheti is the predominant language in Unakoti and North Tripura districts, in towns like Kailasahar and Dharmanagar. An overwhelming majority of the population in these districts speak Sylheti.

These apart, Bengalis from Sylheti who migrated to India during the Partition and later, and are now Indian citizens, also understand and speak the language. They are spread all over Bengal and India.

Malviya’s first claim about Bengali language — that dialects like Sylheti are incomprehensible to Indian Bengalis — is, therefore, false. In fact, BJP leaders from Assam have taken strong exception to the IT cell chief remarks. “You must be aware that at least 50 Lakh Sylheti-speaking Bengalis reside in India, with the Barak valley alone having a majority population of Sylheti speakers,” BJP Rajya Sabha member from Silchar, Kanad Purkayastha wrote to Malviya. BJP leader and former Silchar MP Rajdeep Roy told TOI, “Over 70 lakh Indians across the Barak Valley, Tripura, and Meghalaya speak Sylheti.”

Claim II: “There is, in fact, no language called “Bengali” that neatly covers all these variants”

Since in the previous sentence Malviya talks about dialects, and then uses the phrase ‘these variants’, it is understood that by variants he refers to the various dialects. Now, the idea of dialects are central to the understanding of any language, not only Bengali or Bangla.

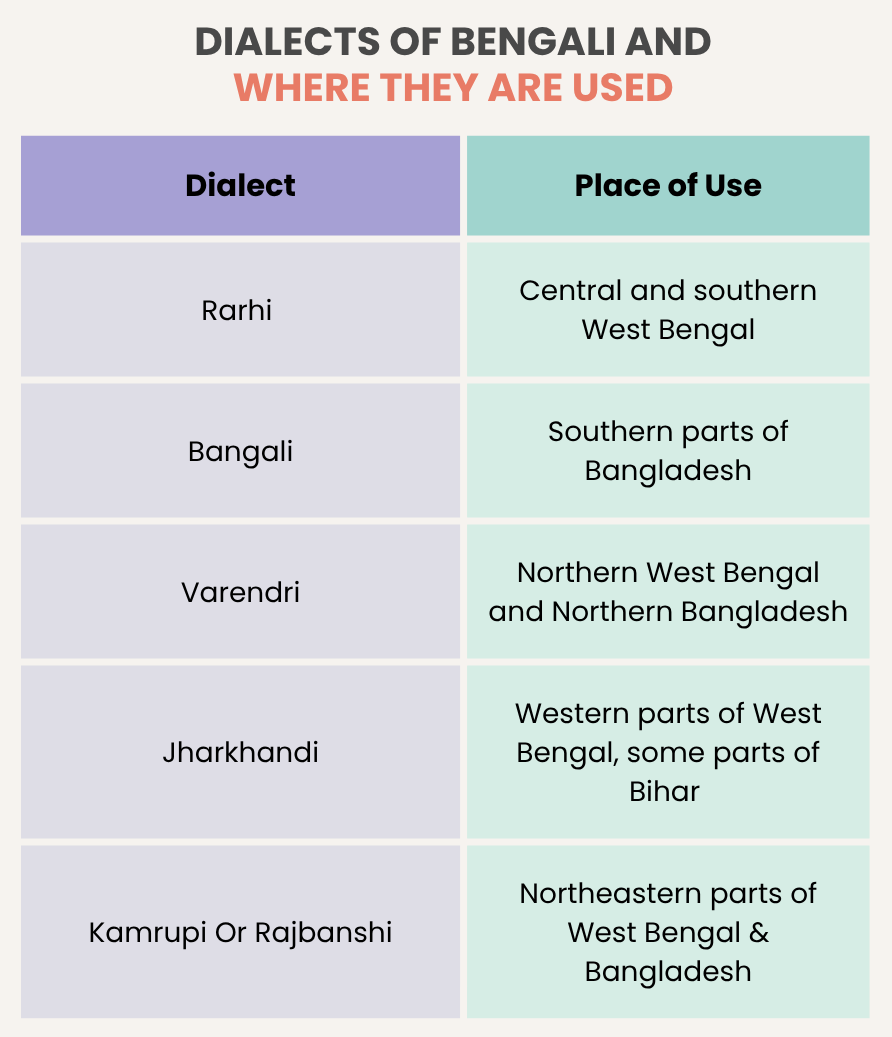

Bengali, a language of the Eastern Indo-Aryan family, which originated from Magadhi Prakrit, has many dialects. And the Term, ‘Bengali’ includes all of them. Dialects refer to variants within a large speech community. Linguist David Crystal defines a dialect thus: “A regionally or socially distinctive variety of language, identified by a particular set of words and grammatical structures.” According to linguist Sukumar Sen, formation of dialects becomes inevitable when a language is spoken by a large number of people. So, if one travels across West Bengal from south to north, one would find that the Bengali spoken in the East and West Midnapore districts are different from that used in Kolkata in vocabulary and intonation. The language spoken in Bankura is different from the one spoken in Purulia, though they are neighbouring districts. Any of these, again, is markedly different from what one would get to hear in Murshidabad. Up north, the language used by people in Siliguri and Jalpaiguri is, again, different from all of these. However, all these are variants or regional dialects of Bengali.

Crystal writes that “the distinction between ‘dialect’ and ‘language’ seems obvious: dialects are subdivisions of languages… the so-called ‘dialects’ of Chinese (Mandarin, Cantonese, etc.) are mutually unintelligible in their spoken form. (They do, however, share the same written language, which is the main reason why one talks of them as ‘dialects of Chinese’.)”

Any book on Bengali linguistics identifies five main regional dialects of Bengali. These are as follows:

While the above are regional dialects, Bengali, like any other language, has several social dialects or social stratificational dialects as well. Social dialects are variants of a language which are dependent on distinctions in social strata.

Then there are individual variants as well known as idolects. An idolect is an individual’s unique and distinct way of speaking, which is defined by their vocabulary, use of grammar, pronunciation etc. Vivekananda and his spiritual teacher Ramakrishna Paramahansa lived during the same time and in the same geographical area for much of their lives, and were in close contact with each other. Yet, they spoke distinctly different idolects. Those were variants of Bengali as well.

The fact that Malviya draws our attention to — that the Bengali spoken somewhere in Bangladesh can be incomprehensible to some in West Bengal — is a phenomenon linguists have duly addressed. In technical parlance, it is called a dialect continuum. Crystal defines it thus: It is “a term used to describe a chain of dialects spoken throughout an area; also called a dialect chain. At any point in the chain, speakers of a dialect can understand the speakers of other dialects who live adjacent to them; but people who live further away may be difficult or impossible to understand. For example, an extensive continuum links the modern dialects of German and Dutch, running from Belgium through the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria to Switzerland.”

In other words, such variants exist in all languages. Bengali, the world’s seventh most spoken language, is no exception. It doesn’t take away the fact that Bengali is still the language that includes all these variants.

Claim III: “Bengali” Denotes Ethnicity, not Linguistic Uniformity”

The fact check of Claim II already proves that Bengali denotes linguistic uniformity. Not only that, contrary to what Malviya claims, as a language, it acts as a unifier for people belonging to diverse ethnic groups. Marwaris, Biharis, Odias, Gujaratis, Parsis who are settled in various parts of Bengal for generations speak the language and are bound together with son-of-the-soil Bengalis by dint of the shared language.

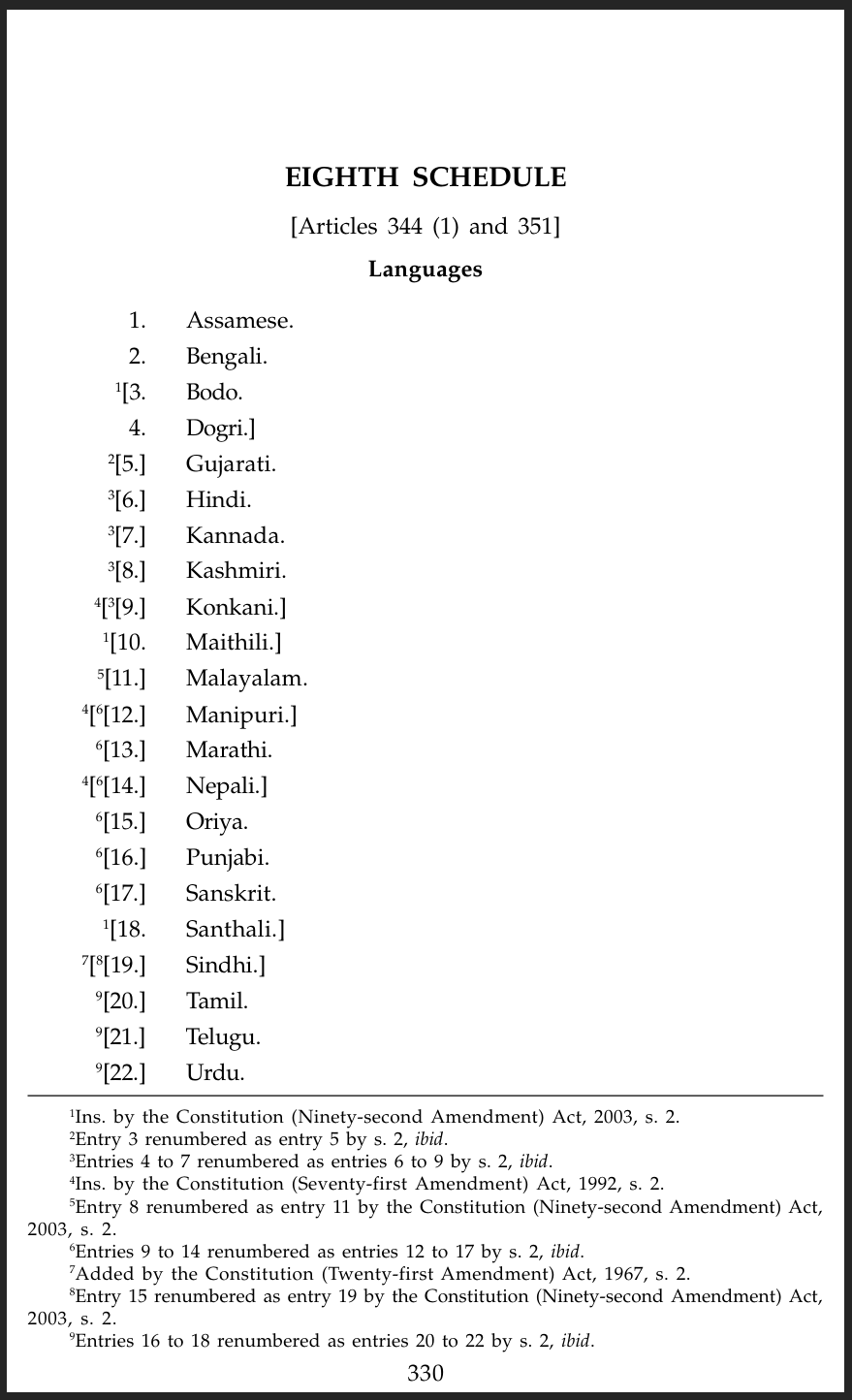

The Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which lists languages officially recognized by the Government of India, mentions Bengali as one of them.

In October 2024, the Union Cabinet led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi awarded ‘Classical Language’ status to Bengali, calling it “one of India’s most prominent languages, (which) holds a significant place in the cultural and linguistic history of the subcontinent.” The formal announcement said, “This designation acknowledges Bengali (referring to the language) as a custodian of India’s ancient cultural legacy, preserving its rich history, literature, and traditions…”

‘Bengali Literature’ Includes Works from Bangladesh

Even a cursory glance at the gems of Bengali literature will confirm that ‘Bengali’ denotes linguistic uniformity. The classics of Bengali literature include pieces written by Indian Bengali authors as well as Bangladeshi writers. The title of the first chapter and the opening few lines of Agunpakhi (quoted below), a modern-day classic by Bangladeshi fiction writer Hasan Azizul Haque, have many words that a Kolkata-born Bengali of the present generation would not be familiar with. Yet, no one in their sane mind doubts the place of Agunpakhi (published in 2006) in the canon of modern Bengali classics. This is possible because of the linguistic uniformity of Bengali despite its many dialects and variants.

“ভাই কাঁকালে পুঁটুলি হলো

আমার মায়ের য্যাকন মিত্যু হলো আমার বয়েস ত্যাকন আট-ল বছর হবে। ভাইটোর বয়েস দেড়-দু বছর। এই দুই ভাই-বুনকে অকূলে ভাসিয়ে মা আমার চোখ বুজল। ত্যাকনকার দিনে কে যি কিসে মরত ধরবার বাগ ছিল না। এত রোগের নামও ত্যাকন জানত না লোকে।”

Nazrul Islam, an Indian poet born in Burdwan district of what is now West Bengal, is the national poet of Bangladesh. A song written by an Indian poet is Bangladesh’s national anthem. Internationally, cultural personalities from West Bengal and Bangladesh are both referred to as Bengali poets, filmmakers and authors. When poet Shamsur Rahman passed away, the BBC report described him as the foremost poets of contemporary Bengali literature, and not Bangladeshi literature. The Hollywood Reporter, one of the word’s premier publications on film and arts, referred to Humayun Ahmed as a “famous Bengali writer” when they published a piece titled ‘The Best Movies in the World’ in 2012.

All these are irrefutable evidence of Bengali denoting ‘linguistic uniformity’.

Claim IV: “So When the Delhi Police Uses “Bangladeshi language,” it is a Shorthand for the Linguistic Markers Used to Profile Illegal Immigrants from Bangladesh”

This part of the statement defies logic. How could Delhi Police, which needed the help of a translator to understand the text in question, identify the linguistic markers which distinguished the various dialectical and syntactic conventions of Bengali language used in India from those used in Bangladesh? One also fails to understand how linguistic markers can be used to ‘profile illegal immigrants’.

Besides, according to the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, its national language is Bangla or Bengali. There is no linguistic entity called ‘Bangladeshi language’.

Logic has Left the Building

It is also to be noted the central logic behind Malviya’s whole argument while defending the phraseology of the letter — that the Bengali spoken in Bangladesh is phonologically different from that used in West Bengal — is irrelevant in the present context.

It is not applicable because Delhi Police is not talking about the phonology or speech sounds. Malviya writes, “The term (Bangladeshi language) is being used to describe a set of dialects, syntax, and speech patterns that are distinctly different from the Bangla spoken in India.” He misses (or maybe ignores) the simple point that the letter concerns itself with the written and not spoken language. It is a written text or texts that the officer wanted translated in Hindi or English. He called it “text written in Bangladeshi language” and wanted a translator “proficient in Bangladeshi national language”. Phonology, or the study of speech sounds, here, is of no relevance.

Even if we set aside the questions of relevance and logical tenability for a moment, this claim, too, is factually incorrect like every other claim made in the X post. The Bengali spoken in Chittagong in Bangladesh might be phonologically different from the Bengali spoken Purulia in West Bengal, but anyone who is familiar with the Bengali spoken in the streets of Dhaka would know that apart from a few minor differences in choice of a handful of words (mainly verbs), it is the almost same language that is spoken in Kolkata.

To cut a long story short, Malviya is trying to defend the indefensible.

Sources:

- Bhashar Itibritto, Sukumar Sen, Eastern Publishers, Kolkata 1968

- Phonology of Sylheti, an Overview, Abu Saleh Md Manjur Ahmed, Aligarh Journal of Linguistics, Vol 11, Aligarh Muslim University, New Delhi, 2021-22

- Sadharon Bhasha Bigyan O Bangla Bhasha, Rameswar Shaw, Pustak Bipani, Kolkata, 1983

- A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 6th Edition, David Crystal, Blackwell, 2008

Independent journalism that speaks truth to power and is free of corporate and political control is possible only when people start contributing towards the same. Please consider donating towards this endeavour to fight fake news and misinformation.