Addressing a large crowd at a Gita recitation event on December 7 at Kolkata’s Brigade parade ground, West Bengal governor C V Ananda Bose made the claim that Hindi was India’s ‘rashtra bhasha’ or national language.

The programme, called Panch Lakhhya Kanthe Gita Path (Gita chanting by five lakh voices) was organised by an outfit named Sanatan Sanskriti Sansad. It was attended by several prominent faces associated with the Right wing, including Sadhvi Ritambhara, Dhirendra Shastri, Kartik Maharaj as well as BJP leaders such as Union minister Sukanta Majumdar, state BJP chief Shamik Bhattacharya, Bengal Opposition leader Suvendu Adhikari, ex-MPs Dilip Ghosh and Locket Chatterjee and MLA Agnimitra Paul.

The event saw religious gurus and BJP leaders unanimously calling for ‘Hindu unity’ at a time when Hindus, according to them, were becoming ‘outsiders’ in Bengal. Bengal Opposition leader Adhikari claimed that chief minister Mamata Banerjee had been invited to the programme, but she chose not to attend because “Trinamool believes in the politics of appeasement only.”

The governor, in his address, quoted extensively from the Gita and referred to the Indian epics. Reminding the audience that “something” had happened in Murshidabad the previous day, he urged them to end “religious arrogance” in the state. Bengal was in a sad state of affairs and was ready to usher in change, he remarked.

At the very beginning of his speech, he said, “I will try to speak in Hindi, since Hindi is our national language. The national language is the mother. English is a midwife, and a midwife can never be a mother.”

India does not have a National Language

Is Hindi India’s national language? The answer is no. In fact, India does not have a national language.

The Constituent Assembly had intense debates on September 12, 13 and 14, 1949, under the chairmanship of President Dr. Rajendra Prasad on the question of official language/s of the Union and the language of higher judiciary. While some members preferred a ‘one language and one script’ formula and suggested that Hindi should replace English, some others, particularly from South India, opposed this vehemently.

T A Ramalingam Chettiar from Tamil Nadu, for example, asked, “What will it be like when we, giving up our own languages, adopt the language of the North, go back to our provinces and face our electorates?” Jawaharlal Nehru objected to the perception that “Hindi-speaking area(s) were “the centre of things in India, the centre of gravity, and others being just the fringes..” He said, “That is not only an incorrect approach, but it is a dangerous approach… this approach will do more injury to the development of the Hindi language than the other approach. You just cannot force any language down the people or group who resist that.”

Eventually, both Hindi and English were adopted as official languages of the Union for a period of 15 years.

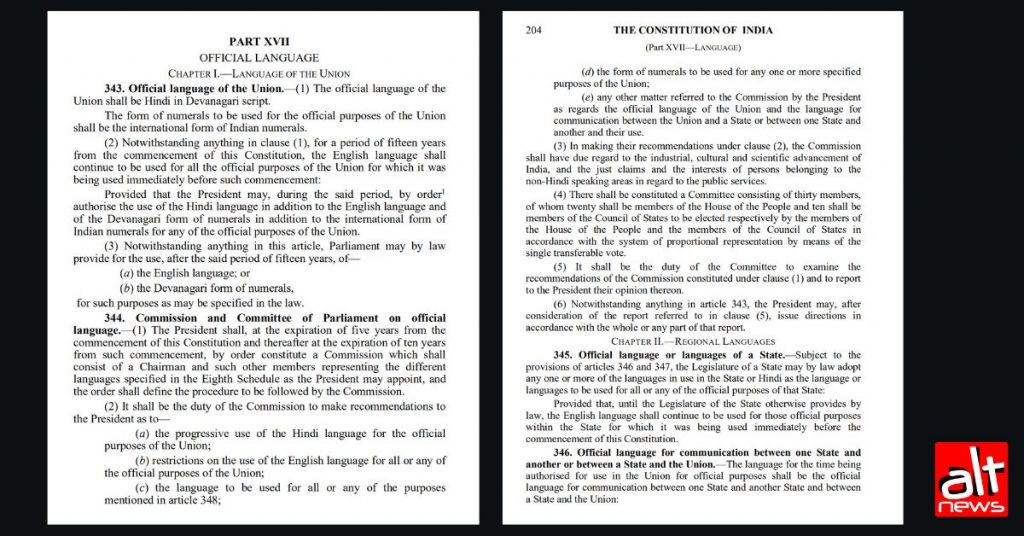

Part XVII of the Constitution of India, which comprises Articles 343 to 351, contains the relevant provisions. Article 343 says, “The official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script. The form of numerals to be used for the official purposes of the Union shall be the international form of Indian numerals.

Notwithstanding anything in clause (1), for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union…”

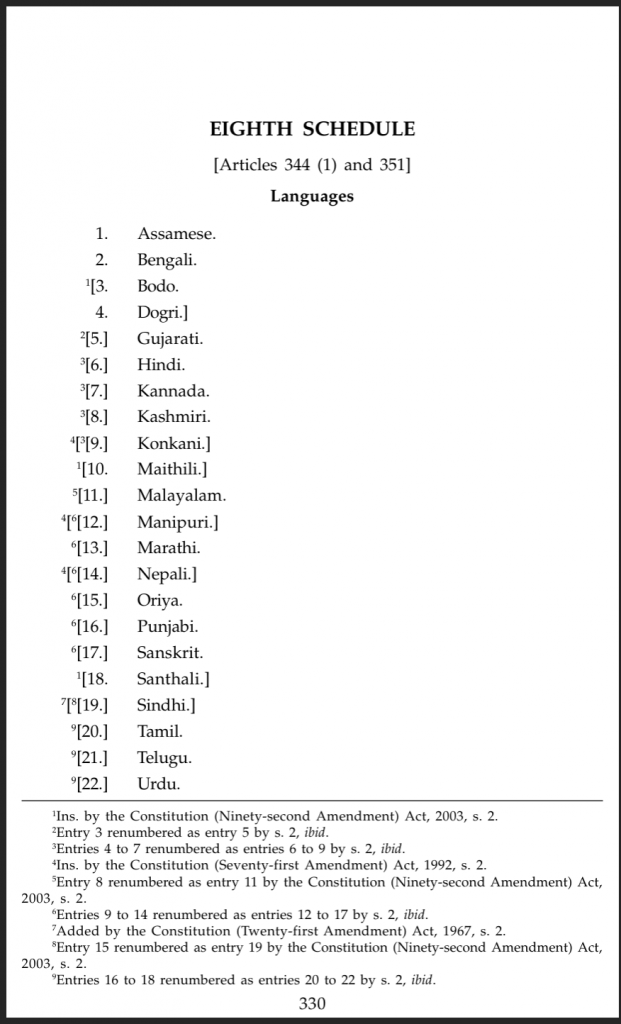

Subsequently, Article 344 mentions that “The President shall, at the expiration of five years from the commencement of this Constitution and thereafter at the expiration of ten years from such commencement, by order constitute a Commission which shall consist of a Chairman and such other members representing the different languages specified in the Eighth Schedule as the President may appoint, and the order shall define the procedure to be followed by the Commission.”

The Eighth Schedule of the Constitution officially recognizes 22 languages. These are Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Bodo, Santhali, Maithili and Dogri.

It is also important to note that the Official Languages Act, 1963 made English a permanent associate official language alongside Hindi for the Union government, overriding the initial 15-year phase mentioned in the Constitution. It states, “Notwithstanding the expiration of the period of fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution, the English language may, as from the appointed day, continue to be used in addition to Hindi, (a) for all the official purposes of the Union…”

In other words, this Act allows Hindi and English for all official purposes of the Union, Parliament, central/state acts, and high courts, thus preventing Hindi imposition and maintaining bilingualism.

Further, Article 347 states that if a substantial number of persons speak a certain language in a state and demand official recognition of the same, the President shall look into that and if satisfied, they shall ‘direct that such language shall also be officially recognised throughout that State or any part thereof for such purpose as he may specify’.

In simpler terms, the Constitution of India does not, at any point, specify any language as the national language of the country.

Gujarat HC Spelt it out Clearly in 2010

In a 2010 judgment, the Gujarat high court made it crystal clear that Hindi was not the national language of India.

Noting that while many people might assume or accept Hindi as the national language, a Bench of Chief Justice S J Mukhopadhaya and justice A S Dave observed that no constitutional provision or official order established it as such. The observation came during the dismissal of a PIL seeking to make manufacturers print product details — such as price, ingredients, and manufacturing dates — exclusively in Hindi.

The court pointed out that the Constitution placed Hindi in the Devanagari script and English under the category of official languages in Article 343, not national languages. It also referred to debates in the Constituent Assembly, which ultimately rejected a proposal to designate Hindustani as the national language. Additionally, the court highlighted that existing packaging rules already allow declarations either in Hindi or in English, making further directions unnecessary.

Independent journalism that speaks truth to power and is free of corporate and political control is possible only when people start contributing towards the same. Please consider donating towards this endeavour to fight fake news and misinformation.