On December 15, when social media content creator and ad agency employee Prashant’s phone started buzzing with notifications, he thought it was some recent post attracting a lot of engagement. However, his excitement soon turned into panic when he found out the reality.

Over the course of the next few days, Prashant and his partner, Shrishti, an educator by profession, would witness their lives get dissected to pieces on social media. The hounding and trauma that the content creator duo had to suffer for making a video on Israeli soldiers vacationing in India is just one part of the problem. The more crucial issue came up when they tried to address their problem legally. The challenges they faced there was a tell-tale indicator of gaping loopholes in the existing Indian legal framework to address cyberbullying, harassment and doxing.

A heap of personal information about them was scraped from the internet, leaked on platforms like X, and weaponised. Fabricated narratives were created to vilify Prashant’s queer identity. False claims about their personal life and professional conduct were disseminated. Emails were sent to Shrishti’s workplace with demands for her to be fired. Private email IDs, phone numbers and even office IDs were made public.

Over the course of their efforts to take legal action against their harassers, Shrishti and Prashant realised that social media platform policies and the Indian legal system offered little means to address such menaces.

How It All Started

On December 9, 2025, Shrishti and Prashant posted a video on Instagram on the practice of Israeli soldiers vacationing in India as part of their “Post-Army Big Trip” or detox holidays. Large numbers of Israeli soldiers travel to India every year, particularly to places like Goa, Dharamkot, Kasol, Pushkar, and Himachal, after completing their military service. These holidays are usually state-sanctioned. The couple states in their video that these destinations have developed Israeli enclaves and tourism infrastructure catering specifically to them, with some hostels displaying Israeli Defence Force (IDF) symbols.

This practice, Shrishti and Prashant claim, is indicative of a broader ideological alignment between the current Indian and Israeli governments, by dint of which India is considered a safe haven for Israeli soldiers amid the ongoing war in Gaza.

Prashant and Shrishti, who regularly post explainer videos on socio-political issues ranging from caste and religion to the war in Gaza, said the video received a whopping 2.6 million views — something that had never happened before. The couple cumulatively gained over 18,000 followers as a result.

However, their nightmare started on December 15. “On Instagram, we were expecting some trolling, and we received some pushback for the first two to three days after posting our video. We also got a lot of support. However, around the 13th (of December), the video was shared on X by a prominent handle without our consent. In the post, they highlighted my septum piercing in an attempt to mock me. But that was just one handle. After that, it started dying down both on Instagram and X. So we were a little relieved. But on the 15th (of December), we saw a lot of Right-wing pages with thousands of followers posting our video on X, and that’s when the hounding started,” Prashant told Alt News.

According to the couple, initially, the trolling manifested in abuses on Instargram. Soon after, their contact details were leaked. “We had to make our profiles private, we were getting emails, we were getting abusive comments, my number was leaked… They even found my Substack and tried to abuse me there as well. That’s when we decided that it is best to deactivate our accounts.”

Below is a gallery of X posts that targeted the content creator duo. As readers can see, they were called ‘psychopaths’, ‘terrorists’, ‘criminals’, ‘a***oles’, ‘inciters of violence’, ‘b**ches’, ‘closet jihadist’ and so on.

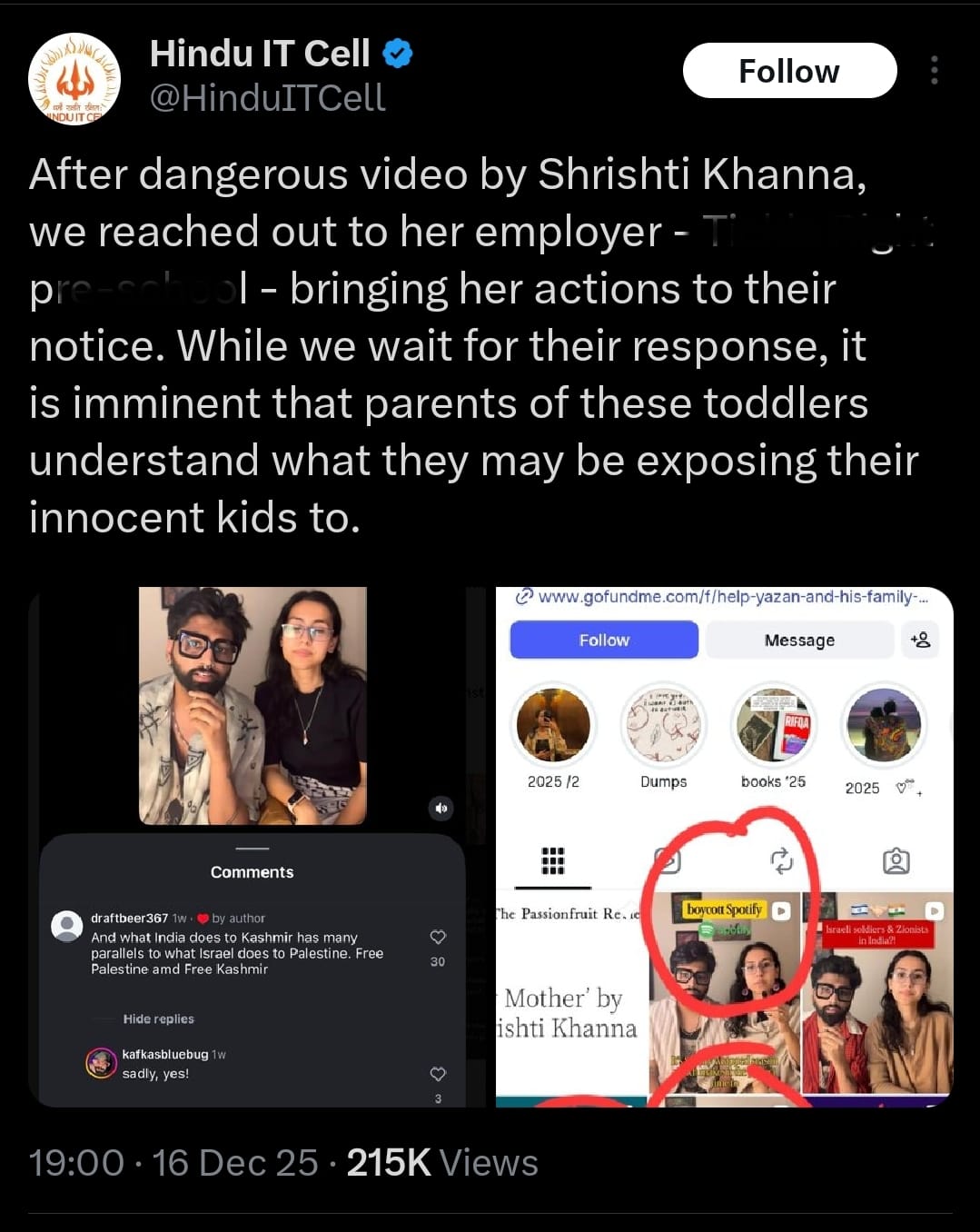

The situation further escalated after troll accounts on X identified Shrishti’s workplace, a children’s school. She became the target of posts that publicly named the institution and urged her employers to take note of her “dangerous politics”.

“My workplace confirmed that they had received emails about me. I have made videos for them in the past. My employers, who are active on social media, were asked to take down my videos. I was contacted by my workplace on two occasions regarding the harassment that they had faced. They were getting comments asking to fire me. Questions were raised about what kind of a teacher I was and whether I was radicalising the children,” recounted Shrishti.

Taking things one step further, X user @HinduITCell started the rumour that Shrishti had been fired from her job. This was entirely false, Shrishti told Alt News.

Right Wing propaganda outlet OpIndia went so far as to ‘report’ that Shrishti had been “sacked” after a video in which she allegedly “targeted” Israeli tourists. India Times referred to Shrishti as ‘Female Umar Khalid’ in its report. News aggregator app Dailyhunt republished the India Times article. Following legal notices, both India Times and Dailyhunt took down their stories. OpIndia, however, has not.

Prashant’s number and office email ID were also leaked. “My work email is not in the public domain. I do not know how they found it,” he said.

“When we posted the video on Instagram, it reached a lot of people, and we were getting hateful comments. We are not active anywhere but on Instagram. However, when the trolls on X picked it up, it became a proper coordinated harassment where people were being directed to our Instagram account to find out more information, take screenshots, find out what we are saying, and take our previous videos as well. Then they started doxing us, and we started getting threats. So we deactivated our accounts, but it didn’t really help because they moved on to LinkedIn and used whatever they could find. There was a website that I had registered on as a tutor to find freelance work. They also found that, and I had to delete my complete profile from there as well. But that also didn’t really help because they had already found some details. We write pop culture articles for a website. They even found the owner of the website and started harassing and abusing her,” Shrishti recounted.

“We could see a pattern in the attacks and realize that they were trying to make sure that we lose our jobs,” Prashant added.

On being asked if they reported the X posts, Prashant said, “Given the policies of X, we believed that they would do something since our personal information were being leaked. Also, the video that was being shared, we didn’t want it on X, and they had a policy for that as well. We reported several posts. But not a single post was taken down. My inbox was full of emails from X and every single email stated that the posts I reported had not violated the platform’s policy. Then you sort of hit a dead end, right? You realise that these platforms are the perfect enablers for the bullies because there are no repercussions. They are protected by the platform.”

Platform Issues

A careful look at X’s Private Content policy reveals that X does not consider the dissemination of publicly available information doxing unless a home address has been shared. It states, “If the reported information was shared somewhere else before it was shared on X, such as someone sharing their personal phone number on their own publicly accessible website, we may not consider this information to be private, as the owner has made it publicly available elsewhere. However, we may take action against home addresses being shared, even if they are publicly available, due to the potential for physical harm.”

In other words, if your phone number is mentioned somewhere on your LinkedIn profile, and if some X user digs it out from there, posts it on X and asks their followers to call and abuse you, X won’t call it doxing. Unlike in earlier cases of doxing (explicitly leaking phone numbers, addresses), harassers these days use this gap in X’s policy and weaponize information that is already shared on some other platform in some other context to incite abusive behaviour and harassment against an individual.

At the same time, the list of someone else’s private information that can’t be shared without permission from the concerned person includes “contact information, such as non-public personal phone numbers, email addresses.” The platform also states that its priority is to prevent potential physical harm and that it takes into account the intent behind sharing of information. Yet, inexplicably, the sharing of a workplace details of the content creators with the obvious motive of intimidating them and drive them out of jobs was not considered a violation by the platform.

Readers would agree that doxing should be taken seriously because the exposure of someone’s identifying information such as workplace address poses a real-life threat to their safety. In today’s digital world, privacy of information is already a much compromised idea. An advanced search on Google or on a social media platform reveals a lot about an individual in an instant. Hence strict laws and their proper implementation are required to stop the misuse of personal details.

Shrishti and Prashant’s ordeal and the callousness with which the platform treated their grievances underscore the ineffectiveness of X’s private content policy.

Legal Loopholes

Having exhausted platform remedies, Shrishti and Prashant sought legal help. They were asked to file cyber complaints against their harassers. However, here, too, they hit roadblocks. Indian law addresses doxing only indirectly through some scattered provisions of the Information Technology Act and the Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita. Moreover, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act excludes data that is already “publicly available.”

Section 78 of the BNS criminalizes stalking (including persistent online tracking or contact), Section 79 addresses privacy violations against women, Section 356 covers defamation, and Section 294 may apply to vulgar or humiliating content. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act) mandates explicit consent for the collection, processing, and sharing of personal data. However, Section 3 clearly excludes data that has been “made or caused to be made publicly available” by the user whose information is being shared — the loophole exploited in almost every doxing case.

We spoke to Swati Khanna, advocate for Prashant and Shrishti, who explained that multiple cyber complaints had already been filed seeking registration of FIRs against those harassing and threatening them. Srishti and Prashant are in touch with the police regarding the same.

“There are two kinds of legal remedies available in such cases: civil and criminal. Civil remedies include filing civil defamation suits seeking damages and/or injunctions. Sending legal notices acts as a formal warning, and in some instances, recipients have taken down their posts/articles after receiving such notices. We intend to send legal notices to a few more individuals/organizations whom we have identified as having caused legal injury to my clients,” Khanna said.

Civil remedies are easier to pursue when the individuals behind the offending content can be clearly identified, she pointed out.

“However, criminal remedies are crucial in this case because the harassment went beyond defamatory content and included criminal intimidation in the form of rape threats and death threats, which are criminal offences. In criminal proceedings, the objective is punishment rather than compensation. So criminal complaints have been filed against a few X users, Instagram Users, and a YouTube podcast host, including against some anonymous social-media handles,” the lawyer told Alt News.

Addressing the delay in FIR registration, Khanna noted that filing a criminal complaint did not always immediately result in an FIR. The police may conduct a preliminary inquiry before registering an FIR, particularly in cyber cases. However, when a complaint discloses cognizable offences such as criminal intimidation or online harassment, the law mandates registering an FIR.

“The online anonymity poses practical legal challenges. When the identity of the harasser is unknown, civil remedies become difficult, unless the courts direct social media platforms/intermediaries like X, Instagram, etc. to identify such online offenders, take down such posts and suspend such accounts. Criminal law, however, allows complaints against unknown persons,” she further stated, adding, “In case, FIRs are not registered in this case, we may be compelled to file a complaint before the magistrate to ensure that the matter is taken to its legal conclusion and that the law is enforced.”

Doxing? Defamation? or No Offence at all?

On being asked if defamation cases can cover cases of doxing, Apar Gupta, the founder of Internet Freedom Foundation, explained that the law by itself did not have any specific provision for doxing. So defamation is often used as a proxy for the vacuum in the law.

But there is a problem there as well.

“For a defamation case, the information that is being used to dox a person is not as important as the surrounding phrasing or the content that is posted alongside the personal information”, he said. For instance, Gupta explained, if there’s no accompanying statement that amounts to lowering a person’s reputation, then the case for defamation itself is not there,” he said.

“The ingredient for the constitution of an offence of defamation is lowering somebody’s reputation by words, actions, or phrases, or gestures. Now, if there is no such comment but only a person’s phone number or address, then that’s doxing, and that’s outside the bounds of defamation”, Gupta added.

Any legal process also has its financial implications. Shrishti and Prashant told Alt News that they lacked the financial means to pursue legal action against every perpetrator. They are therefore forced to “choose” only a handful, typically the most vicious accounts, to proceed against.

Taken together, this combination of systemic constraints, the intermediary platform’s reluctance to intervene, and the legal system’s limited understanding of the fast-evolving, dynamic nature of doxing in digital spaces effectively grant online trolls a free run. Shielded by anonymity and fake profiles, they can dig up and weaponize personal information with little fear of consequence.

We asked Gupta why the platforms were not serious about tackling issues of doxing and cyberbullying. Had such issues been addressed at the platform level, suers could have been spared the trouble of initiating and following up on hectic, time-consuming and costly legal processes.

“I would say that platforms generally do contain within their content moderation policies provisions for the prohibition of using personal information of another person. Such terms of service need to be implemented through their content moderation practices”, said Gupta.

“What we have witnessed over the last few years is that platforms have systematically underinvested in content moderation, preferring to implement it through artificial intelligence or machine learning algorithms. So whenever the user makes a complaint about a violation of the terms of service, that complaint is judged by an algorithm through machine learning. There’s also an absence of dedicated resource line or help centres which are available. It’s a systematic issue, with regard to the number of content moderation issues, which also includes abuse through fake imagery, which is artificially generated, and threats of violence. So doxing is a part of a wider dysfunction in social media, and platforms are not able to ensure that the conversations happening on them are safe, or respectful — or are not illegal at the very least.”

On January 17, 2024, Shaviya Sharma, an NRI woman, commented on a post by X user Squint Neon regarding an interview of Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath. Her post went viral, following which several troll accounts, including Squint Neon, revealed her personal data, professional identity and photographs. Similar to the case of Shrishti and Prashant, the harassers tagged Sharma’s employer in their posts, demanding that strict action be taken against her. An email was sent to her employer discussing her “online conduct”.

Sharma took Squint Neon to court, following which, the Delhi high court, while expressing sympathy to the plaintiff, held that her situation did not legally constitute “doxing” because her original X post contained her initials and profile picture, rendering her partially identifiable. Nevertheless, the Court granted substantial relief: It directed X to remove offending posts and disclose Basic Subscriber Information (BSI) of the harassing accounts, and ordered disclosure of details linked to a suspicious email used to contact her employer.

Independent journalism that speaks truth to power and is free of corporate and political control is possible only when people start contributing towards the same. Please consider donating towards this endeavour to fight fake news and misinformation.