What’s in a name? Apparently, a lot, if social media trends and raging political discourses are anything to go by. The India vs. Bharat debate has caught the fancy of the entire nation with several prominent social media users (BJP leaders, Right Wing accounts, celebrities) claiming that the name ‘India’ is a colonial relic, or, given by the British.

The debate has gained currency against the backdrop of the Opposition alliance naming itself I.N.D.I.A. The name was announced after 26 parties had met in Bengaluru on July 18. On the same day, BJP leader and Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sharma said in a tweet, “The British named our country as India. We must strive to free ourselves from colonial legacies. Our forefathers fought for Bharat, and we will continue to work for Bharat.”

Our civilisational conflict is pivoted around India and Bharat.The British named our country as India. We must strive to free ourselves from colonial legacies. Our forefathers fought for Bharat, and we will continue to work for Bharat .

BJP for BHARAT

— Himanta Biswa Sarma (@himantabiswa) July 18, 2023

He subsequently changed his bio on X (formerly Twitter) from ‘chief minister of Assam, India’ to ‘chief minister of Assam, Bharat.’

While the government convening a special session of the Parliament from September 18 without initially divulging the agenda kept everyone guessing for some time, a G20 invitation mentioning the unusual phrase ‘President of Bharat‘ and a document related to PM Modi’s Indonesia visit describing him as the ‘Prime Minister of Bharat‘ further fueled speculation. On September 10, the wreath that PM Modi placed at Mahatma Gandhi’s final resting place at Rajghat had ‘the Republic of Bharat‘ written on it. At the G20 conference table, the nameplate in front of PM Modi said ‘Bharat’.

BJP’s U-Turn on ‘Bharat’

For the last nine years of his two stints as PM, Narendra Modi has been the ‘Prime Minister of India’. Several schemes and campaigns brought in by his government have had ‘India’ in their names — Digital India, Make in India, Khelo India, Startup India, so on and so forth.

It is also worth noting that in 2004, the Mulayam Singh Yadav-led SP government in Uttar Pradesh had passed a resolution to amend Article 1 of the Constitution to say ‘Bharat, that is India’, and not of ‘India, that is Bharat’. According to reports, (1, 2, 3) the resolution was accepted unanimously in the state legislative assembly, expect by the BJP lawmakers, who staged a walk out.

Moreover, in November 2015, the Modi-led NDA government told the Supreme Court that the country did not have to be called ‘Bharat’ instead of ‘India’. Responding to a PIL seeking a declaration that the Republic be called ‘Bharat’ for official and unofficial purposes by Union and state governments, the Centre claimed “there is no change in circumstances to consider any change in Article 1 of the Constitution of India.”

In view of this, it is difficult not to see the sudden volte-face and the new-found love for ‘Bharat’ as a knee-jerk reaction to the Opposition alliance naming itself I.N.D.I.A.

India or Bharat? A Debate Dating Back to 1949

After Independence, the Constituent Assembly took almost three years to complete the historic task of drafting the Constitution of India. During this period, it held eleven sessions covering a total of 165 days. Of these, 114 days were spent on the consideration of the Draft Constitution.

The Draft of Article 1 of the Indian Constitution, which starts with the sentence “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States“, was debated in the constituent assembly on November 15 & 17, 1948, and later again on September 17 & 18, 1949.

On November 15, 1948 during a debate in the Constitution Hall (later known as the Central Hall of the Parliament), Ananthasayanam Ayyangar, who would later serve as the first deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha, wanted to rename ‘India‘ to ‘Bharat’. On September 18, 1949, member H V Kamath introduced an amendment to use both ‘India’ and ‘Bharat’. The drafting committee chairman, B R Ambedkar, through an amendment, had already suggested that the Draft Article say ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States’.

Kamath was not particularly happy with this phraseology. He found the construction, “India, that is Bharat’, ‘somewhat clumsy‘. He was not the only one. “India, that is, Bharat’ are not beautiful words for, the name of a country. We should have put the words “Bharat known as India also in foreign countries”, said Seth Govind Das.

The proposed amendments were put to vote and eventually Ambedkar’s suggestion, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States” was accepted.

Fact Check: Is ‘India’ a British Coinage?

One of the most viral tweets in this context was by former cricketer Virender Sehwag, who claimed, “We are Bhartiyas, India is a name given by the British…” Referring to an article by himself, senior journalist Prabhu Chawla wrote on X (formerly Twitter), “Let India, a British noun, be buried, and a new Bharat emerge…” BJP MP from Uttar Pradesh Harnath Singh Yadav went a step further and told ANI that the word ‘India’ was an abuse given to us by the British… Adish C Aggarwala, the president of the Supreme Court Bar Association, told PTI that the name India was given by the British. The list continues to grow even as this article is being written.

The World History Encyclopedia has an entry on the ‘Etymology of the Name India‘. It gives us in a nutshell what is the general consensus about the etymology of the word ‘India’:

- “The name of India is a corruption of the word Sindhu. Neighbouring Arabs, Iranians uttered ‘s’ as ‘h’ and called this land Hindu. Greeks pronounced this name as Indus. Sindhu is the name of the Indus River, mentioned in the Rig-Veda, one of the oldest extant Indo-European texts, composed in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent roughly between 1700-1100 BC. There are strong linguistic and cultural similarities with the Iranian Avesta, often associated with the early culture of 2200-1600 BC. The English term is from Greek Ἰνδία (Indía), via Latin India…”

A sweeping glance at the ancient history of India proves that it would be a travesty of truth to say that the name ‘India’ was first used by the British colonizers for the piece of land south of the Himalayas. Historians are almost unanimous in accepting that the word ‘India’ was derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Sindhu’ through multiple intermediate versions, and the Greeks were the first to use it. It is also agreed by most of them that ‘India’ was in use more than 1000 years before the first Briton set foot on our soil. One can cite n-number of primary and secondary historical references that corroborate that the name ‘India’ predates British colonialism in the subcontinent by several centuries. Here are some of them:

- The most straightforward acknowledgement comes from Will Durant. In Chapter XIV Vol 1 of his monumental work ‘The Story of Civilization‘, the American historian and philosopher says that the word India was coined by the Greeks. He writes: “Through the western Punjab runs the mighty river Indus, a thousand miles in length; its name came from the native word for river Sindhu which the Persians (changing it to Hindu) applied to all northern India in their word Hindustan — i.e., “Land of the Rivers.” Out of this Persian term Hindu, the invading Greeks made for us the word India.” (Page 393)

- This theory pertaining to the origin of the word India is agreed upon by Aligarh Muslim University historian Irfan Habib as well. In The Formation of India: Notes on the History of an Idea (Social Scientist, July-August 1997, Vol. 25), Habib writes, “As is well known the ancient Iranian use of the consonant ‘h’ for Indo Aryan ‘s’, led to the Iranian form of ‘Hind(u)’ for the Sanskrit ‘Sindhu’; there after, to the use of the former name for the entire trans-Indus country, whence has come the form ‘India’ through the Greek ‘Indos’…” (Page 6)

- The first Greek historian who writes clearly about India is Hecataeus of Miletus. Hecataeus, alternatively spelt Hekataios, was a predecessor of Herodotus, who wrote extensively about India. In the introduction to ‘Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian‘, which is a translation of the fragments of Megasthenes’ Indika, J W McRindle writes, “The first historian who speaks clearly of it is Hekataios of Miletos (BC 549-486).” In the footnote, he adds, “The following names pertaining to India occur in Hekataios :— the Indus; the Opiai, a race on the banks of the Indus; the Kalatiai, an Indian race; Kaspapyros, a Gandaric city; Argante, a city of India; the Skiapodes, and probably the Pygmies.” (Page 5)

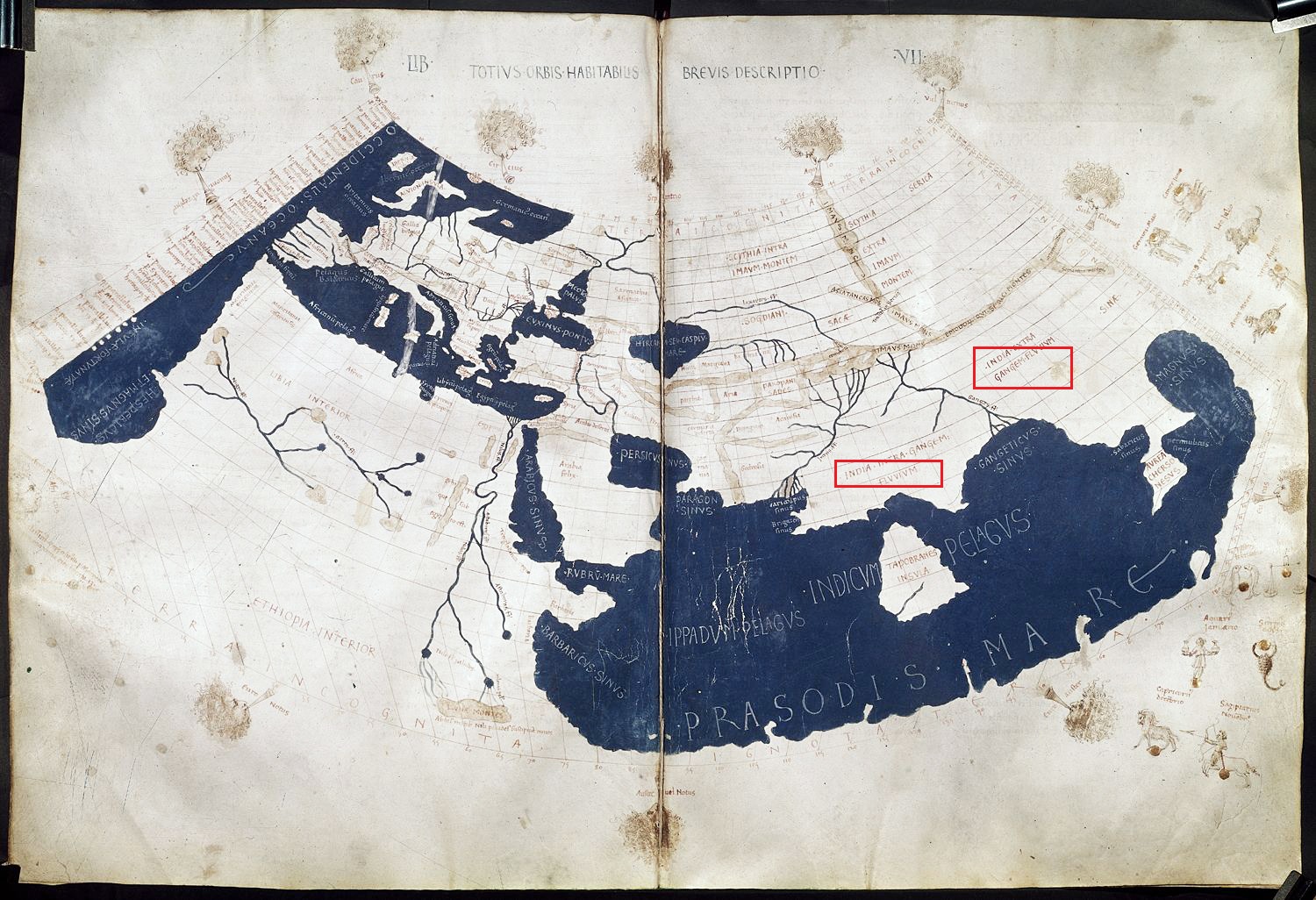

- Based on descriptions contained in Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia (written in Alexandria, circa 150 AD), 2nd Century Greek cartographer Agathodaemon of Alexandria drew a map of the world as it was known to the ancient Romans. The map refers to India as India and depicts it as surrounded by the rivers, the Indus and the Ganges.

Source: Wikimedia Commons - Ctesias of Cnidus, an ancient Greek physician, wrote the first monograph on India based on his personal experiences as he worked as the court physician in Persia. He called the work Indika. He speaks about Indian cheese, wine, scented oil et al. An interesting observation that he makes is that the river Indus, at its narrowest, was as wide as 40 stadia, and at its widest, 200.

- Jawaharlal Nehru acknowledged the debt to the Greeks for the name India. In a letter to Indira on May 8, 1932, later published in the book Glimpses of World History, Nehru writes, “Have I told you, or do you know, how our country came to be called India and Hindustan? Both names come from the river Indus or Sindhu, which thus becomes the river of India. From Sindhu the Greeks called our country Indos, and from this came India. Also from Sindhu, the Persians got Hindu, and from that came Hindustan.” (Page 124)

- In fact, the British themselves have acknowledged the same. In his much acclaimed book The Loss of Hindustan The Invention of India (Harvard University Press, 2020), Columbia University historian Manan Ahmed Asif writes that the venerable William Jones, the British philologist who arrived in Calcutta in 1783 to work as a judge for the British Supreme Court in Fort Williams, Calcutta, argued that “the ‘Sindhu’ from Sanskrit becomes ‘Hindav’ in Old Persian or Avestan, ‘India’ in Greek, ‘Hodduv’ in Hebrew, and later ‘al-Hind’ in Arabic.” (Page 34)

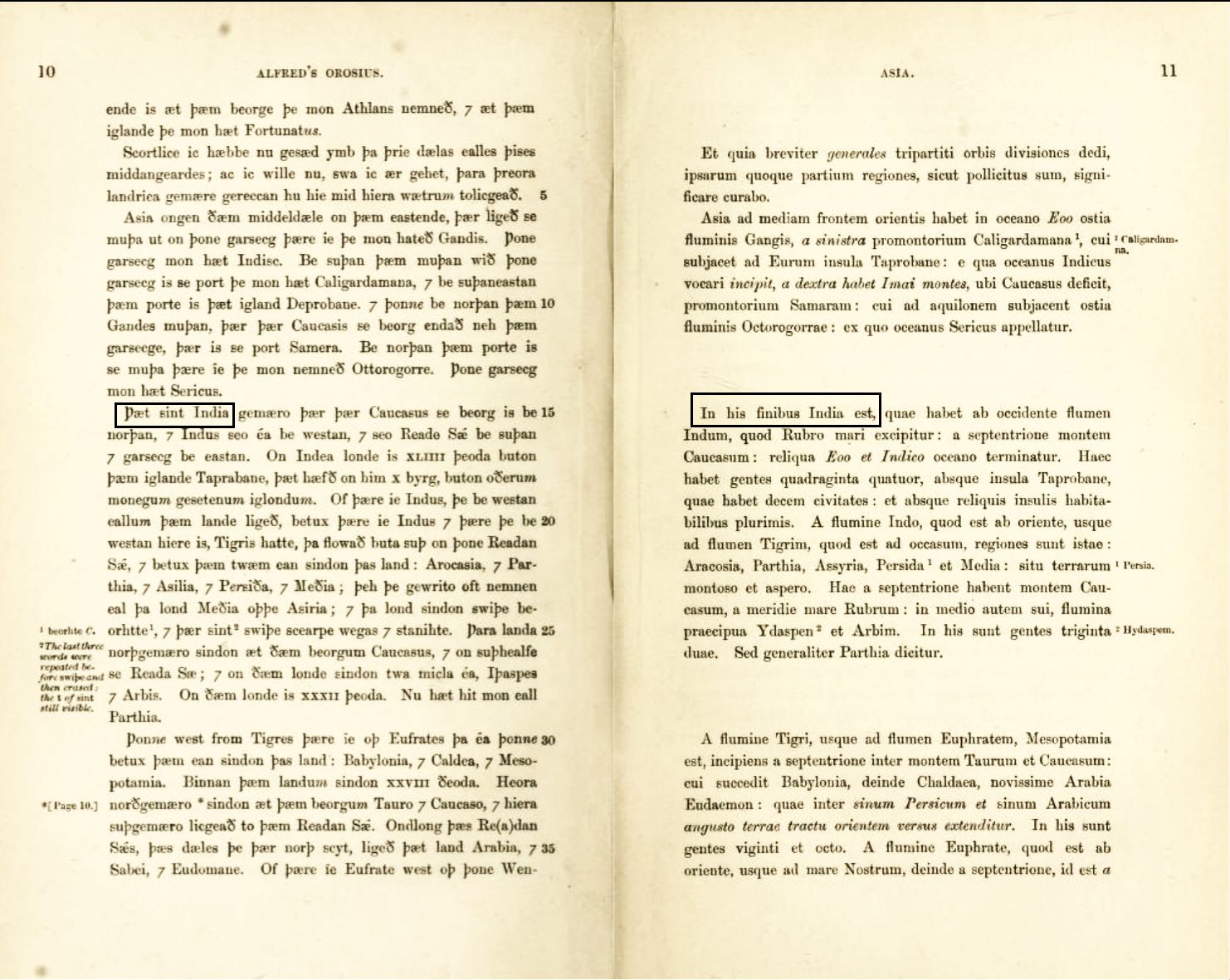

- The name India was known to the 4th Century Latin poet Paolo Orosius. In his seminal work Historiae Adversus Paganos, the word is used in Book 1. The original text can be accessed here, and the modern-day English translation can be read here. The book was translated into the West Saxon dialect in the Old English period by an anonymous scholar under the patronage of King Alfred the Great. This work, known as King Alfred’s Orosius (circa 900 AD) also, consequently, has the word India. An archived version of the book can be accessed here. Below, we have highlighted two instances of the use India from Book 1:

- Manan Ahmed Asif has deliberated on the topic of nomenclature in some detail his book mentioned above. His introduction begins, “What happened to Hindustan? The Portuguese, Dutch, British, and French who visited, settled in, and conquered the subcontinent since the sixteenth century used Estado da Índia, Nederlands Voor-Indië, British India, or Établissements français dans l’Inde to denote their colonial holdings.” (Page 1) In the endnote, he adds, “In 1499, when Vasco da Gama returned to Lisbon from Calicut, Dom Manuel I became “Senhor de Guine e da Conquista Navegação e Comércio de Etiópia, Arábia, Pérsia, e da Índia.” This shows that the word India was used in Portugese and Dutch in the 16th Century.

- The Cambridge History of India (Ed. E J Rapson) cites the 5th Century BC tragedian Aeschylus as the first Greek poet to mention India by its name in the play, ‘The Suppliants’. “In the Greek books which we possess this is the earliest mention of Indians by name.” (Page 394) Rapson also gives us a highly interesting account of how the word India found its way into Greek vocabulary. It says, “In the sixth century BC, the Semitic and other kingdoms of Nearer Asia disappeared before a vast Aryan Empire, the Persian, which touched Greece at one extremity and India at the other. Tribute from Ionia and tribute from the frontier hills of India found its way into the same imperial treasure-houses at Ecbatana or Susa. Contingents from the Greek cities of Asia Minor served in the same armies with levies from the banks of the Indus. From the Persian the name Indoi, ‘Indians,’ now passed into Greek speech. Allusions to India begin to appear in Greek literature.” (Page 391-392)

The Idea of India: Even that Predates the Brits

There is ample reasons to believe that not only the word, but also the idea of India as a political entity predates British colonialism of the subcontinent.

There is a section of historians who hold that the idea of India as a political space comes into being only with colonization. They are of the opinion that “… the British were the first to control or claim the entire territory of the southern peninsula… the subcontinent before British colonization was an age of “regional kingdoms” with no coherent notion of territoriality nor the political control over the entire peninsula. The only noted exceptions are of Ashoka… or the Mughal king Aurangzeb.” (Asif, 3)

This idea is strongly contested by Irfan Habib. In his essay, The Formation of India: Notes on the History of an Idea, Habib discusses the history of the concept of India. Habib suggests that the mention in early Pali texts of the 16 ‘mahajanapads’ in the early 6th Century BC is the first hint that a notion of a country holding together all these regional identities was beginning to emerge. Quoting Ashoka’s rock edicts and the Brahminical legal text Manusmriti (both composed possibly in the 2nd Century BC), Habib argues that “… the perception of India as a country marked by certain social and religious institutions begins to be present only by the time that the Mauryan empire (circa 320-185 BC) was established.” (Page 5)

Habib calls this a significant achievement because “… India was not naturally a country from “times immemorial”; it evolved by cultural and social developments…” (Page 6). Over the next 1000 years, references to India as a well demarcated geographical space, appeared in Sanskrit texts on a regular basis. It is in the 14th Century Sufi poet Amir Khusrau’s writings, that Habib traces the first “explicitly propounded” conception “of a composite culture being the distinguishing feature of India”. Religious differences did exist, but in Khusrau’s insistence on him being “a Hindustani Turk”, and Hind being his “home and native land”, or in the discussions in Nuh Sipihr of India’s contributions to the world and its multiculturalism, Habib sees the clear “perception of India as home to different traditions interacting and adjusting with each other”, a perception that was reinforced by the Mughal emperor Akbar. A significant prerequisite to be identified as a modern nation was thus achieved.

The other important precondition, a sense of political unity, became a reality according to Habib when the “centralizing tendencies of the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire repeatedly projected the sight of a politically unified India.” He writes, and this is enormously significant to our present purpose, “Some prerequisites of nationhood had thus seemingly been achieved by the time that the British conquests began: in 1757, the year of Plassey, India was not only a geographical expression, it was also seen as a cultural entity and a political unit.” (Page 8)

To conclude, both the word India and the idea of India predate the arrival of the British to the subcontinent. To call either of them a British colonial relic is a distortion of history, either done purposefully or out of ignorance.

Independent journalism that speaks truth to power and is free of corporate and political control is possible only when people start contributing towards the same. Please consider donating towards this endeavour to fight fake news and misinformation.